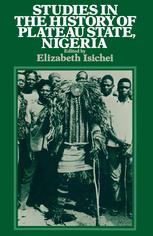

Studies in the History of the Plateau State, Nigeria 🔍

Elizabeth Isichei M.A., D.Phil. (eds.)

Palgrave Macmillan UK, 1, 1982

英语 [en] · PDF · 31.1MB · 1982 · 📘 非小说类图书 · 🚀/lgli/lgrs/nexusstc/zlib · Save

描述

of a historical and ethno- graphic survey of Bendel State, and he contributed to Volume 5 of the Cambridge History of Africa. He has carried out extensive field work in East Afi-ica and the Benue Valley.

century, but all around the Kanuri-speaking area are pockets of Chadic speakers who were, presumably, the original inhabitants of Borno. These include the Buduma of Lake Chad, the Bole, Karekare and Bedde, to the west, and the Tera, Bura and Marghi in Gongola.

In Plateau State there is a large bloc of peoples speaking closely related Chadic languages. The Ngas are the most numerous of these. Traditions recorded in the early 1930s and confirmed by some, but not all, present-day informants, state that the Ngas came ultimately from Barno, and more immediately from Yam. 14 Yam is a town in Kanam, not far to the north-east of the Plains Ngas, which is today inhabited by the Dugurijarawa and which is of continuing ritual importance to both the Ngas and the Boghom. 15 It is thought that the Plains Ngas towns were founded before those of the Hills, which is confirmed by the fact that the Plains towns have the original sacred images. 16 An earlier inquirer-who tried to combine ethnographic research with military conquest-claimed that 'The Angass evince no curiosity about themselves, and in the absence of traditions, one must have recourse to outside arguments .. .' 17 A migration from Borno is not impossible-the Kanuri of Lafia travelled a greater distance in the late eighteenth century-and it is compatible with the linguistic evidence. Could the Ngas have been among the 'So' displaced by the immigrant Kanuri? To the present writer it seems most likely that the Ngas migrated from somewhere north of their present home and that the identification with Borno came later, perhaps at the time of the Bauchi invasions in the nineteenth century, when it seemed attractive to identify with a powerful but conveniently remote state known to be at war with the Sokoto Caliphate.

The Mwahavul polities do not have a single orthodox tradition of origin. But just as Yam looms large in Ngas tradition as a secondary centre of migration, so, for most-though not all-Mwahavul states, Gun or Ngung, eleven miles south-east ofPankshin and near Chip, pla)IS this role. The earliest version of tradition, recorded in 1907, states that Kumbul was the first settlement, followed by Panyam, Kerang and Vodni. Kumbul came from an area about eight miles away. Panyam came from 'Vwom to the N.W. of Chip', and Kerang from much the same area. Am pan came from 'Gun South of Chip'. 18 A version recorded in 1934laid more emphasis on Gun. Kumbul was still thought to have come from close at hand, its people sprung pologised' 44 , and much published and unpublished research has been carried out since then. But the basic problems ofjukun history remain. Was 'Jukun' the same as 'Kwararafa'? How do we explain the apparent paradoxes in Jukun and Kwararafa history?

Kwararafa was a non-Muslim kingdom in the Benue valley. A late fourteenth-century Sarkin Kano invaded it, and it was among the conquests of the perhaps legendary Sauriniyya Amina of Zaria. In the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the Kwararafa invaded Hausaland on a number of occasions. They took both Kano and Katsina, but made no attempt to keep their conquests. The Kanuri knew the same people as the Kwana; Ali Gaji fought them in the late sixteenth century. When a Kwararafa invasion was repelled in the seventeenth, Dan Marina ofKatsina wrote a poem of thanksgiving, which is the only known Arabic or Hausa document identifying the Jukun and Kwararafa. 45 In recent years, the identification of Jukun, Kwana and Kwararafa has been questioned. But Koelle was told of it by an informant who left his homeland in the 182os. 46 Muhammad Bello, writing in c.I813, described Kwararafa as a body of twenty states under one king, which had fought Kano and Borno successfully in the past, and which had gold, salt and antimony minesY If Kwararafa was an alliance, scholars disagree as to the peoples involved. Low, rather unconvincingly, suggests the Tera and Bolewa as those who, with the Jukun, comprised Kwararafa; 48 Webster suggests the Goemai, Alago and Abakwariga. 49 There are many difficulties in all this. By the nineteenth century, the Jukun lived interspersed among other peoples in the Benue valley. Far from being a martial people, they were easily defeated by invading Chamba and Fulani, and only the Jukun of Pindiga remember an earlier warlike past. Unomah 60 makes the interesting suggestion that the invasions of the north were prompted by the quest for slaves, and that in the eighteenth century thejukun turned instead to the exploitation of the resources of the Benue valley. The change from a phase of warlike expansion to one of introspection and religious ritual is well documented in the history of Benin. Sterken sees the Kwararafa invasions of the north as a confrontration between two opposed world views, Islam and traditional religion.al Colonial writers were agreed that thejukun came from far to the north-east. 'They came from the East and probably through Egypt.' 52 Palmer was convinced that they came from Kanem,

century, but all around the Kanuri-speaking area are pockets of Chadic speakers who were, presumably, the original inhabitants of Borno. These include the Buduma of Lake Chad, the Bole, Karekare and Bedde, to the west, and the Tera, Bura and Marghi in Gongola.

In Plateau State there is a large bloc of peoples speaking closely related Chadic languages. The Ngas are the most numerous of these. Traditions recorded in the early 1930s and confirmed by some, but not all, present-day informants, state that the Ngas came ultimately from Barno, and more immediately from Yam. 14 Yam is a town in Kanam, not far to the north-east of the Plains Ngas, which is today inhabited by the Dugurijarawa and which is of continuing ritual importance to both the Ngas and the Boghom. 15 It is thought that the Plains Ngas towns were founded before those of the Hills, which is confirmed by the fact that the Plains towns have the original sacred images. 16 An earlier inquirer-who tried to combine ethnographic research with military conquest-claimed that 'The Angass evince no curiosity about themselves, and in the absence of traditions, one must have recourse to outside arguments .. .' 17 A migration from Borno is not impossible-the Kanuri of Lafia travelled a greater distance in the late eighteenth century-and it is compatible with the linguistic evidence. Could the Ngas have been among the 'So' displaced by the immigrant Kanuri? To the present writer it seems most likely that the Ngas migrated from somewhere north of their present home and that the identification with Borno came later, perhaps at the time of the Bauchi invasions in the nineteenth century, when it seemed attractive to identify with a powerful but conveniently remote state known to be at war with the Sokoto Caliphate.

The Mwahavul polities do not have a single orthodox tradition of origin. But just as Yam looms large in Ngas tradition as a secondary centre of migration, so, for most-though not all-Mwahavul states, Gun or Ngung, eleven miles south-east ofPankshin and near Chip, pla)IS this role. The earliest version of tradition, recorded in 1907, states that Kumbul was the first settlement, followed by Panyam, Kerang and Vodni. Kumbul came from an area about eight miles away. Panyam came from 'Vwom to the N.W. of Chip', and Kerang from much the same area. Am pan came from 'Gun South of Chip'. 18 A version recorded in 1934laid more emphasis on Gun. Kumbul was still thought to have come from close at hand, its people sprung pologised' 44 , and much published and unpublished research has been carried out since then. But the basic problems ofjukun history remain. Was 'Jukun' the same as 'Kwararafa'? How do we explain the apparent paradoxes in Jukun and Kwararafa history?

Kwararafa was a non-Muslim kingdom in the Benue valley. A late fourteenth-century Sarkin Kano invaded it, and it was among the conquests of the perhaps legendary Sauriniyya Amina of Zaria. In the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the Kwararafa invaded Hausaland on a number of occasions. They took both Kano and Katsina, but made no attempt to keep their conquests. The Kanuri knew the same people as the Kwana; Ali Gaji fought them in the late sixteenth century. When a Kwararafa invasion was repelled in the seventeenth, Dan Marina ofKatsina wrote a poem of thanksgiving, which is the only known Arabic or Hausa document identifying the Jukun and Kwararafa. 45 In recent years, the identification of Jukun, Kwana and Kwararafa has been questioned. But Koelle was told of it by an informant who left his homeland in the 182os. 46 Muhammad Bello, writing in c.I813, described Kwararafa as a body of twenty states under one king, which had fought Kano and Borno successfully in the past, and which had gold, salt and antimony minesY If Kwararafa was an alliance, scholars disagree as to the peoples involved. Low, rather unconvincingly, suggests the Tera and Bolewa as those who, with the Jukun, comprised Kwararafa; 48 Webster suggests the Goemai, Alago and Abakwariga. 49 There are many difficulties in all this. By the nineteenth century, the Jukun lived interspersed among other peoples in the Benue valley. Far from being a martial people, they were easily defeated by invading Chamba and Fulani, and only the Jukun of Pindiga remember an earlier warlike past. Unomah 60 makes the interesting suggestion that the invasions of the north were prompted by the quest for slaves, and that in the eighteenth century thejukun turned instead to the exploitation of the resources of the Benue valley. The change from a phase of warlike expansion to one of introspection and religious ritual is well documented in the history of Benin. Sterken sees the Kwararafa invasions of the north as a confrontration between two opposed world views, Islam and traditional religion.al Colonial writers were agreed that thejukun came from far to the north-east. 'They came from the East and probably through Egypt.' 52 Palmer was convinced that they came from Kanem,

备用文件名

lgrsnf/K:\springer\10.1007%2F978-1-349-04749-9.pdf

备用文件名

nexusstc/Studies in the History of Plateau State, Nigeria/cc2ce94802bbb247e64a9f09ba5e7820.pdf

备用文件名

zlib/History/African History/Elizabeth Isichei [Isichei, Elizabeth]/Studies in the History of Plateau State, Nigeria_2669208.pdf

备选作者

Elizabeth Isichei [Isichei, Elizabeth]

备用出版商

Macmillan Education UK

备用出版商

Red Globe Press

备用版本

United Kingdom and Ireland, United Kingdom

元数据中的注释

lg1459732

元数据中的注释

{"edition":"1","isbns":["134904749X","1349047511","9781349047499","9781349047512"],"last_page":288,"publisher":"Palgrave Macmillan"}

备用描述

Front Matter....Pages i-xvi

Introduction....Pages 1-57

Prologue to Art History in Plateau State....Pages 58-66

Movements of Peoples in Pengana District from Earliest Times to 1960....Pages 67-84

Proverbs as a Mirror of Traditional Birom Life and Thought....Pages 85-89

Towards a Yergam History: Some Explorations....Pages 90-97

The Goemai and their Neighbours: an Historical Analysis....Pages 98-107

The Alago Kingdoms: a Political History....Pages 108-122

The Gwandara Settlements of Lafia to 1900....Pages 123-135

Plateau Societies’ Resistance to Jihadist Penetration....Pages 136-150

The Lowlands Salt Industry....Pages 151-178

Tin Mining on the Plateau before 1920....Pages 179-190

The Fulani Settlement of Butu, Slavery and the Trade in Slaves....Pages 191-205

Colonialism Resisted....Pages 206-223

The Growth of Islam and Christianity: the Pyem Experience....Pages 224-241

Some Changing Patterns of Ngas Response to Christianity....Pages 242-253

Changes and Continuities 1906–39....Pages 254-281

Back Matter....Pages 283-288

Introduction....Pages 1-57

Prologue to Art History in Plateau State....Pages 58-66

Movements of Peoples in Pengana District from Earliest Times to 1960....Pages 67-84

Proverbs as a Mirror of Traditional Birom Life and Thought....Pages 85-89

Towards a Yergam History: Some Explorations....Pages 90-97

The Goemai and their Neighbours: an Historical Analysis....Pages 98-107

The Alago Kingdoms: a Political History....Pages 108-122

The Gwandara Settlements of Lafia to 1900....Pages 123-135

Plateau Societies’ Resistance to Jihadist Penetration....Pages 136-150

The Lowlands Salt Industry....Pages 151-178

Tin Mining on the Plateau before 1920....Pages 179-190

The Fulani Settlement of Butu, Slavery and the Trade in Slaves....Pages 191-205

Colonialism Resisted....Pages 206-223

The Growth of Islam and Christianity: the Pyem Experience....Pages 224-241

Some Changing Patterns of Ngas Response to Christianity....Pages 242-253

Changes and Continuities 1906–39....Pages 254-281

Back Matter....Pages 283-288

开源日期

2016-03-14

🚀 快速下载

成为会员以支持书籍、论文等的长期保存。为了感谢您对我们的支持,您将获得高速下载权益。❤️

如果您在本月捐款,您将获得双倍的快速下载次数。

🐢 低速下载

由可信的合作方提供。 更多信息请参见常见问题解答。 (可能需要验证浏览器——无限次下载!)

- 低速服务器(合作方提供) #1 (稍快但需要排队)

- 低速服务器(合作方提供) #2 (稍快但需要排队)

- 低速服务器(合作方提供) #3 (稍快但需要排队)

- 低速服务器(合作方提供) #4 (稍快但需要排队)

- 低速服务器(合作方提供) #5 (无需排队,但可能非常慢)

- 低速服务器(合作方提供) #6 (无需排队,但可能非常慢)

- 低速服务器(合作方提供) #7 (无需排队,但可能非常慢)

- 低速服务器(合作方提供) #8 (无需排队,但可能非常慢)

- 低速服务器(合作方提供) #9 (无需排队,但可能非常慢)

- 下载后: 在我们的查看器中打开

所有选项下载的文件都相同,应该可以安全使用。即使这样,从互联网下载文件时始终要小心。例如,确保您的设备更新及时。

外部下载

-

对于大文件,我们建议使用下载管理器以防止中断。

推荐的下载管理器:JDownloader -

您将需要一个电子书或 PDF 阅读器来打开文件,具体取决于文件格式。

推荐的电子书阅读器:Anna的档案在线查看器、ReadEra和Calibre -

使用在线工具进行格式转换。

推荐的转换工具:CloudConvert和PrintFriendly -

您可以将 PDF 和 EPUB 文件发送到您的 Kindle 或 Kobo 电子阅读器。

推荐的工具:亚马逊的“发送到 Kindle”和djazz 的“发送到 Kobo/Kindle” -

支持作者和图书馆

✍️ 如果您喜欢这个并且能够负担得起,请考虑购买原版,或直接支持作者。

📚 如果您当地的图书馆有这本书,请考虑在那里免费借阅。

下面的文字仅以英文继续。

总下载量:

“文件的MD5”是根据文件内容计算出的哈希值,并且基于该内容具有相当的唯一性。我们这里索引的所有影子图书馆都主要使用MD5来标识文件。

一个文件可能会出现在多个影子图书馆中。有关我们编译的各种数据集的信息,请参见数据集页面。

有关此文件的详细信息,请查看其JSON 文件。 Live/debug JSON version. Live/debug page.